How to Win at Losing

The consequences of shifting right with the Rahm Emanuel playbook

On my way to work yesterday, the line “crime’s a feeling, a sense of a — a place of mind” came through my headphones. I would place this as a 90s G-funk lyric, except that I was listening to a podcast and it was delivered by Rahm Emanuel, US Ambassador to Japan, longtime Democratic operative, and former congressman and mayor of Chicago. I was struck by these words since the common formulation is actually that safety is a feeling – crime, real or perceived, contributes to that feeling. But I don’t think Emanuel misspoke: as the rest of his appearance on The Ezra Klein Show show demonstrated, he represents the major wing of the Democratic Party that predominantly, if not exclusively, sees politics as vibes. Respond to the right vibes in the right way, and you can win. What you do after winning? Well…

Last week I wrote about the hollowness of the Kamala campaign slogan “Let’s Win This” and what it suggested about this Democratic party:

“The slogan reflects not just the inadequacy of the campaign’s message, but the nature of how this Democratic party runs campaigns. For the consultants and staff behind these decisions, elections are fundamentally a sport between two teams. The consequence of “being sad about losing” is far more salient than the consequences of gutted social programs, mass deportations, or attacks on workers rights…The party understands campaigns as a microtargeting game of margins, not a vehicle for movement-building and social transformation. All of the rhetorical focus on winning, and so little on what we’re actually trying to win.”

While I focused in that newsletter about the particulars of the last four years, Emanuel’s analysis this week offers an excellent synopsis of the last forty years of responsive, hollow Democratic party strategy: win the next election, no matter the ideological cost.

Emanuel’s position is often referred to as triangulation – when “a political candidate presents his or her views as being above and between the left and right sides of the political spectrum” – but I think that’s an overly generous analogy for the reality of American politics. There is no triangle, no third option, in American politics. In practice, this strategy has been a calculation about how far to the right a Democratic politician should shift in order to win votes. As Emanuel puts it to Klein, “you wanted the terrain to be on your side, and we minimized the terrain on their side. That’s how you develop a strategy.”

But this rightward-shift strategy is only an approach to winning a given election. Much less discussed is how this campaign strategy fits into a broader theory of change about how politics, power, and policy interact.

Interrogating the possible theories of change at work here helps to show how the real cost in the long term is not just losing ideologically, but politically and materially. Tellingly, I have to construct my own interpretation of the Emanuel theory of change, because he doesn’t explain himself how his campaign strategy pairs with a governing strategy.

I think there are a few ways this strategy turns to complete incoherence, but let’s propose what it looks like when deployed in a coherent theory of change:

The Right-Shift Theory of Change

Campaign: Shift your message to the right in order to get elected.

Assumption: You can retain your base while adding more conservative voters.

Government: Pass some right-wing policies along with others.

Assumption: Policies will not alienate base & will satisfy conservatives.

Incumbent campaign: Campaign on right-shifted policies and messages.

Assumption: You retain comparative trust on core issues.

Government: Pass another mix of right-wing and other policies.

Assumption: Legacy of this successful government will lead to further electoral gains for the party.

The overarching idea here is to neutralize the perception that Republicans offer any significant alternative. By doing so, Democrats can get elected and pass policy agendas that include their priorities, even if some concessions are required to maintain the reputation needed to get re-elected.

This theory of change never takes off when the first assumption is false (see: innumerable failed Democratic campaigns). It also falls apart – both to challengers from the left and the right – when incumbents misunderstand either (a) the progressive commitments, or (b) the conservative ravenousness of constituents. But the most adept politicians and strategists, in the right contexts, can make it work.

When it succeeds is what’s really at stake here: the most likely outcome of this theory of change is further consolidation of policy and ideology to the right, just under a Democratic banner. This is because the short term fact of winning does not reckon with the long-term impacts of winning that way and with those policies. The Emanuel wing of the party has no interest in that reckoning. Presenting his vision of what Democrats need to return to, Emanuel yearned for Clintonism:

Fact: Bill Clinton, first Democrat to get re-elected since Franklin Delano Roosevelt. That’s a fact. Second, from 1968 to 1988, 20-year run, outside of Jimmy Carter, the Republicans run the presidency, and they run on law and order under Richard Nixon, welfare queens under Ronald Reagan and Willie Horton under George Herbert Walker Bush.

Bill Clinton, from Arkansas, comes along and solves the riddle of these holes, what we would call cultures, but crime, drugs, immigration and welfare. Now we can go through the policies, argue certain things, but he not only gets re-elected, which is one measure of success, but he also sets in a period of time — I think it’s six out of the last seven presidential elections — Democrats win a majority of votes.

I’m not saying he’s totally responsible for it, but it sets a pattern. And rather than learn the lesson of how we solved a 20-year problem for the party that had weighed on Michael Dukakis, weighed on every other candidate prior to that, we totally shunt his presidency aside.”

Setting aside that he’s really talking about a 16 year problem and not 20 (poor Jimmy), Emanuel is praising Clinton’s “lesson” because he gets re-elected, and suggests we not “go through the policies, argue certain things.”

I am interested in going through the policy, arguing certain things. The legacy of those policies demonstrate why this theory is so destructive and self-destructive.

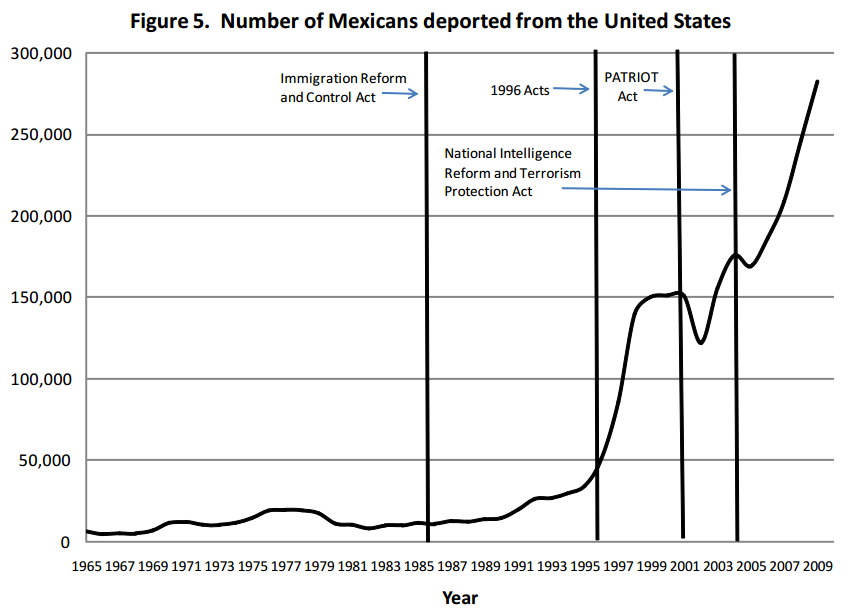

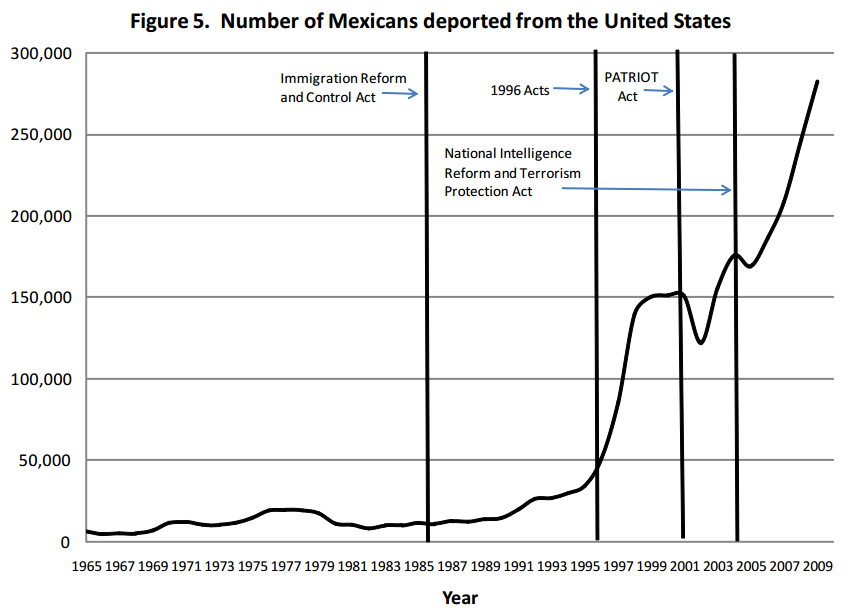

Setting aside the debate one could have about the legacy of NAFTA (1993), Clinton is responsible for major crime and immigration legislation that has had disastrous long-term outcomes for Democrats and for all Americans. Clinton passed “the crime bill” (The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, sponsored by Senator Joe Biden) in 1994 and both the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) and Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) in 1996. The crime bill, among other things, fueled a real prison construction boom and surge of policing in schools, but it also centered a new bi-partisan consensus on punitive “solutions” to crime. Since the public is particularly “mushy” when it comes to both the perception of crime and opinions of crime policy, this massive legislation was a strong signal about what mattered and what to do about it. Meanwhile, the duet of laws from 1996 not only created the modern detention and deportation framework, it was crucial to the effort to equalize unauthorized migration with criminality and danger.

The ascent of Donald Trump depends on these rightward shifts. Far from satisfying conservative energies, they deepened and spread them from the center of power. Far from neutralizing Republican’s ability to differentiate themselves, these shifts neutralized Democrats ability to differentiate themselves. The GOP can always go further right, and Donald Trump now intends to use Clinton (and Obama and Biden’s) tools at his disposal to that end. It turns out that collaborating on a politics of fear and danger does not produce a feeling of safety – it expands the terrain for a strongman. This theory of change ultimately means that when we’re winning elections we’re losing policy and ideology, and when we’re losing elections, we’re losing it all.

And that’s when someone can pull it off, successfully if temporarily suggesting a Democratic renaissance. Most of the time, including the most recent election, there’s no coherent theory at all. Gabriel Winant perfectly summarizes the chaos sown by a party without a sustainable theory of politics and power:

“The demobilization of the Democratic electorate is thus the product of the party’s contradictory character at more than one level. The accountability of the Democrats to antagonistic constituencies produces both rhetorical incoherence—what does this party stand for?—and programmatic self-cancellation. Champions of the domestic rule of law and the rules-based international order, they engaged in a spectacular series of violations of domestic and international law. Promising a new New Deal, they admonished voters to be grateful for how well they were already doing economically. Each step taken by the party’s policymakers in pursuit of one goal imposes a limit in another direction. It is by this dynamic that a decade of (appropriate) anti-Trump hysteria led first to the adoption of parts of Trump’s program by the Democrats, and then finally his reinstallation as president at new heights of public opinion favorability. Nothing better than the real thing.”

The alternative to these failures is not unknown or untested. FDR, famously, cycled from progressive messages to progressive policy to progressive message to progressive policy. To avoid the rightward death spiral, Democrats have to recombine ideology and policy into a recognizable project. In a memo to “Disgruntled Democrats™” this week Waleed Shahid explains what this will take:

The tension between transactional politics and transformational movements is as old as American democracy itself, and today’s Democratic Party is no exception. In moments of upheaval, ideologically driven movements have often dragged their parties out of complacency and into purpose. Abolitionists gave Republicans emancipation. Labor unions handed Roosevelt the New Deal. Civil rights leaders pushed Johnson to deliver the Great Society. Right-wing economists armed Reagan with trickle-down economics. For progressives today, the challenge is to offer not just another interest group to triangulate, but a clear and compelling answer to the most urgent question of our time: “How should Democrats govern?”

Instead of simply interpreting and responding to vibes, this kind of politics creates vibes through clear narrative and corresponding policy that changes people’s lives for the better. That theory of change operates like a clear message: you tell the public what you’re going to do, you do it, and you tell them what you did. Then you win and the public wins, too. Emanuel’s was on the podcast and is under consideration for the next DNC chair because of the perception he knows how to win elections. It’s worth talking about all the other things he also knows how to lose.