Meetings Make Movements

Meetings are how we build collective power. We can craft them accordingly.

Whether or not Oscar Wilde actually said that “the trouble with socialism is that it takes up too many evenings,” it’s useful to say that he did. Since Wilde was both a committed socialist and committed to a good evening, the quip speaks to the underlying tension between the structure and organization necessary to hold people together in collective efforts and, well, the pleasure of doing whatever the hell you want.

The holy grail is, as much as possible, making the collective effort into the pleasurable thing that people actually want to do.

Since ideological affinity is sufficient for a core of people to show up and stick around, however, our movements and political groups aren’t always focused on the experiential factors that would make participation more appealing and accessible to a broader crowd (and more enjoyable to the die-hards, too). While socials, shows, and parties are great ideas for fostering connections and bringing in new people, what we’re connecting all these people around is the trickier, and most crucial, challenge. Whether we like it or not, doing collective work requires meetings. Building any kind of power to meet this moment is going to require a ton of them.

It doesn’t seem sexy to talk about (yet…), but meetings are the core activity of movements. Better meetings mean we better inform, activate, and retain people; better meetings mean better culture, better action, and better strategy. Movements train people to have 1:1 conversations and talk to press and to organize protests. We should treat the art of meeting with just as much care.

You could listen to what I say here because I’ve been in a ton of meetings, I read about them, and I plan and facilitate them for my work – but you’ll listen to me mostly because what I say will build from what you’ve already felt when meetings go poorly and when they’re run well.

A good meeting is hard to find…

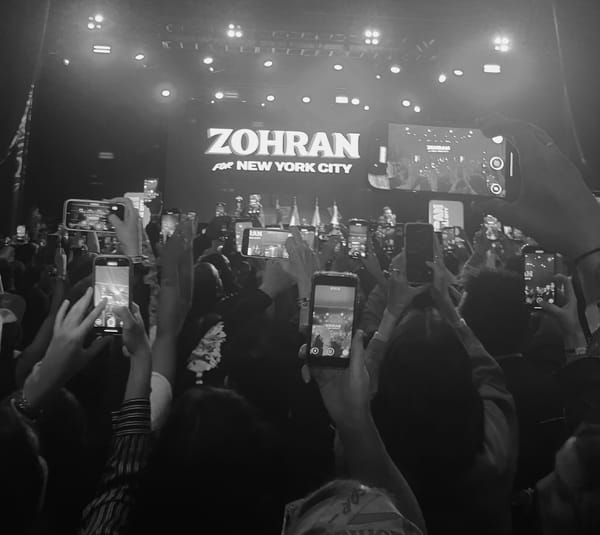

I want to offer an example of one recent meeting – the November general meeting for the Central Brooklyn chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America – as an example of that care. I think this is a useful example not because it was the kind of trainwreck we need to avoid, but because it was pretty good! It was maybe even great for the veterans of the kinds of slogfests and clusterfucks that can be common in organizing and politics. Even so, my hope is that we’re able to create meetings that are great for average people attending a meeting for the first time, people who chose to be there instead of on Netflix or at the bar. We need to be able to convince them to make that choice again.

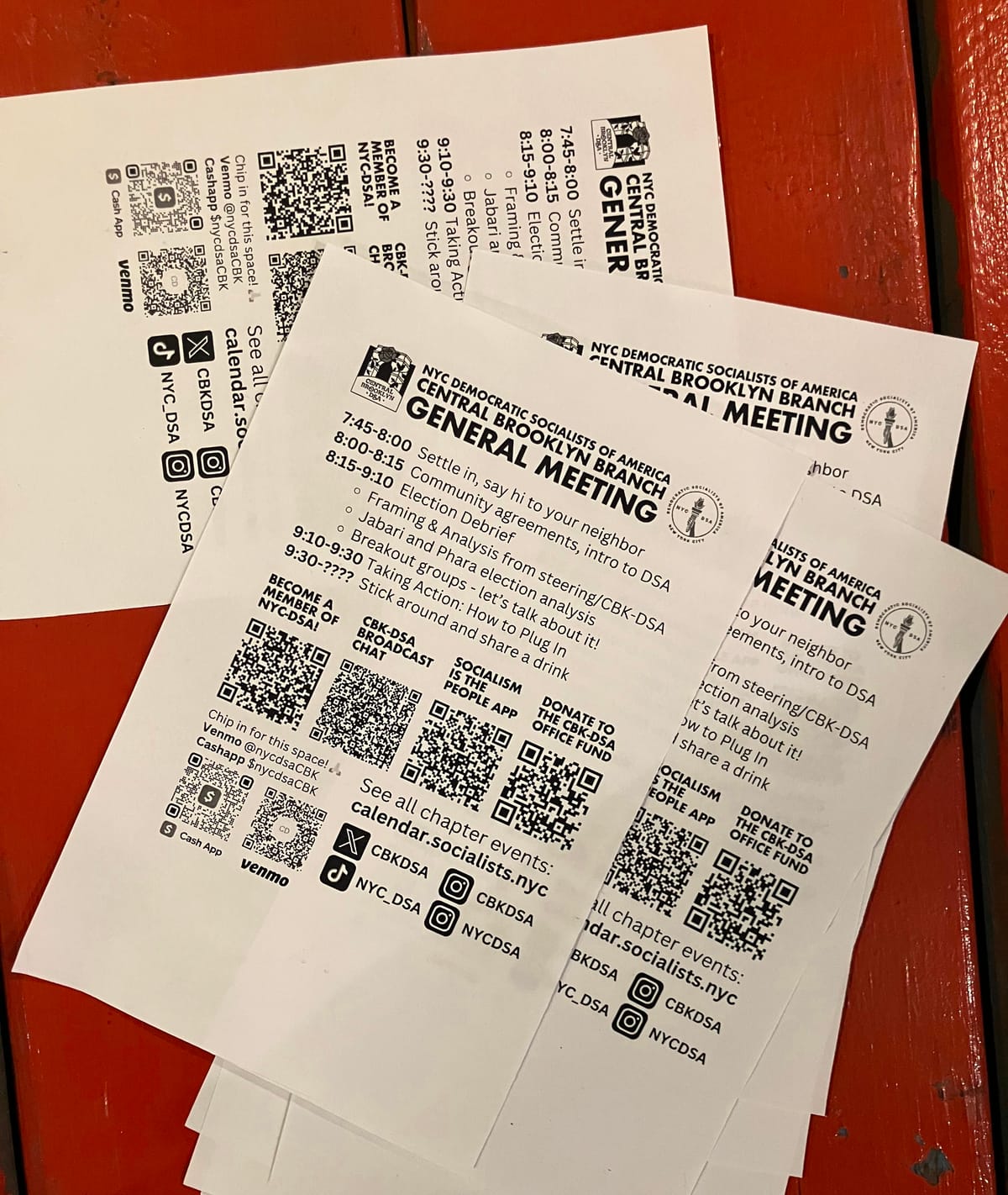

This particular meeting was held in the backroom-of-a-bar-slash-kendo-dojo in Central Brooklyn and had a higher than expected attendance of around ~150 people. People sat in rows or stood facing a projector screen and a microphone at the front of the room. The agenda was printed on flyers as follows:

7:45-8:00 Settle in, say hi to your neighbor

8:00-8:15 Community agreements, intro to DSA

8:15-9:10 Election debrief

Framing & analysis from steering/CBK-DSA

State Senator Jabari Brisport and State Assemblymember Phara Souffrant Forrest election analysis

Breakout groups

9:10-9:30 Taking Action: How to Plug in

9:30-??? Stick around and share a drink

There were very strong parts of this meeting, starting with the fact that this agenda basically held, with the meeting ending just slightly late. One and a half hours is an accessible ask and sticking to that ask respects the tacit agreement made when participants decide to attend a meeting. The organizers also asked people in leadership to identify themselves, as well as asking people attending a DSA meeting for the first time to raise their hands – both great moves for clarifying who can has information and who may need information. The opening section helpfully defined socialism and introduced DSA, which may have been new to some participants but was also a welcome regrounding to regulars. The election debrief section involved a series of slides narrated by leadership showing how Central Brooklyn shifted in the election; followed by engaging comments from two elected socialists who represent the area. Following a brief Q&A, people were split into groups for discussion facilitated by a designated volunteer – a smart bulwark against chaos and a good way to increase connection among attendees. Sharebacks from the group discussions then allowed a greater diversity of voices in the room and produced a sense of common analysis. To close the meeting, representatives of different committees and working groups offered a bunch of different ways for people to continue to take action, a crucial step for converting one meeting into something more. One of the lead facilitators then made a donation ask and closed the meeting, inviting people to stay for the social. Throughout it was clear the organizers had an eye on the clock, jumping-in to keep people on time or cutting inessential sections (like individual introductions of everyone on a committee).

I think that most people had a positive experience at this meeting! There are a few infrastructural tweaks that could have improved it, including: buttons or nametags that visually identified the leadership intended to be identifiable; a fun buzzer or alarm system that could both keep people on time and add some levity; and some kind of refreshment, even if just water mixed with some flavor in a big ol’ cooler. Still, in the full scope of meetings, this meeting was a success.

…but a great meeting isn't hard to form

If we want to make this a great meeting, we can follow the intuition of the organizers and the needs of a a big, diverse room. There were problems with the agenda design which, if you listened closely, you would have heard the organizers acknowledge to everyone from the front of the room. Multiple times someone with the microphone said something to the effect of “we’re giving you too much information”; after an extended presentation section, one said “well, that was boring” of their own presentation. Simultaneously delivering information while knowing you’re doing it poorly is not an uncommon problem, but it is avoidable. If you listened closely, you would also have heard only a small percentage of people in the room saying anything, and a much smaller percentage saying anything to the whole room.

For a revised agenda, I would aim to increase the ability of participants to absorb and act on information, plus shake up when and how people are participating individually, in groups, and as a collective. Here’s how it would go:

Pair discussion: Instruction to chat with someone new next to you based on a grounding prompt like “what brought you here tonight?”

Comments from State Senator Jabari Brisport and State Assemblymember Phara Souffrant

Community agreements & intro to DSA

Take action announcements #1: 1-2 ways to get connected, ideally related to the preceding section.

Election analysis Pt. 1: brief presentation on the broad themes

Take action announcements #2: 1-2 ways to get connected, ideally related to the preceding section.

Small groups

Election analysis Pt. 2: a handout or information from the facilitator on the remaining analysis

Discussion

Shareback

Take action announcements #3: 1-2 ways to get connected, ideally related to the preceding section.

Closing “ceremony”: some kind of collective activity that everyone participates in, whether it’s a song, chant, clap, etc.

What do these changes do? Overall, we’re splitting up passive, individual listening time with active pair, group, and interactive sections. A prompted pair discussion simultaneously offers (a) new connections, (b) grounding in shared motivations, and (c) practice with what organizing looks like. Breaking up the ways to take action breaks “too much information” into distinguishable opportunities; splitting up the analysis reduces the likelihood it will get boring and increases the likelihood people with different learning styles can absorb content.

We’re also changing how the meeting starts and ends. It’s a maxim of facilitator Priya Parker to never start a meeting with logistics, which is an idea that’s almost never followed but is a fundamentally solid one. The advertised feature of this meeting was to hear from the chapter’s elected socialists in office and they are perfect way to make a first impression on new participants and, more broadly, energize the room. Their existence in office and presence at the meeting epitomizes the theme of the agenda and does not need to be blunted or preceded by logistical or organizational information. The rest of the meeting then builds on how we should think about and move towards winning even more of that power.

To close, although we are in a collective space, we have not yet done something altogether. One thing that distinguishes a meeting from daily life – particularly a large one – is the opportunity do the same thing simultaneously with other people. Particularly for people living secular lives, it is a rare opportunity to feel a kind “collective effervescence” of communal belonging and action. Our meetings need to take advantage of that opportunity through collaborative ritual and activity. This meeting should end with everyone in the room saying, singing, or doing some kind of action together – a practice that builds both individual affiliation with a group and expresses overall group unity. That’s the last formal moment of the meeting, not other kinds of logistics (e.g. fundraising or otherwise), and it transitions into collective socializing.

Would these changes make this meeting more traditionally “fun” than whatever else someone may be doing on a given Wednesday night? They would not, but they would help reduce the ways that our meetings can resemble the work of the day time and offer qualities that other ways to spend an evening can not. Would these changes immediately make the left more powerful? Not immediately. But I do believe that we have the talent and creativity in our movements to have better meetings, that better meetings mean better participation and more retention, and that more people is our only real way to people power.

PS: DSA is the largest socialist organization in America; NYC DSA has the largest city membership; Central Brooklyn is the largest chapter. But the chapter does not have reliable space where it can build roots in community and, yes, have (good) meetings. You can contribute here to help secure the rental of a storefront office space for the chapter: http://bit.ly/cbkoffice.

Thanks for reading Stephen’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.