Squid Game Season 2 is testing you

Don't mistake a game for the world, when the world is the game

< This essay does not contain spoilers…but is about S2 in its entirety. Do what you want! >

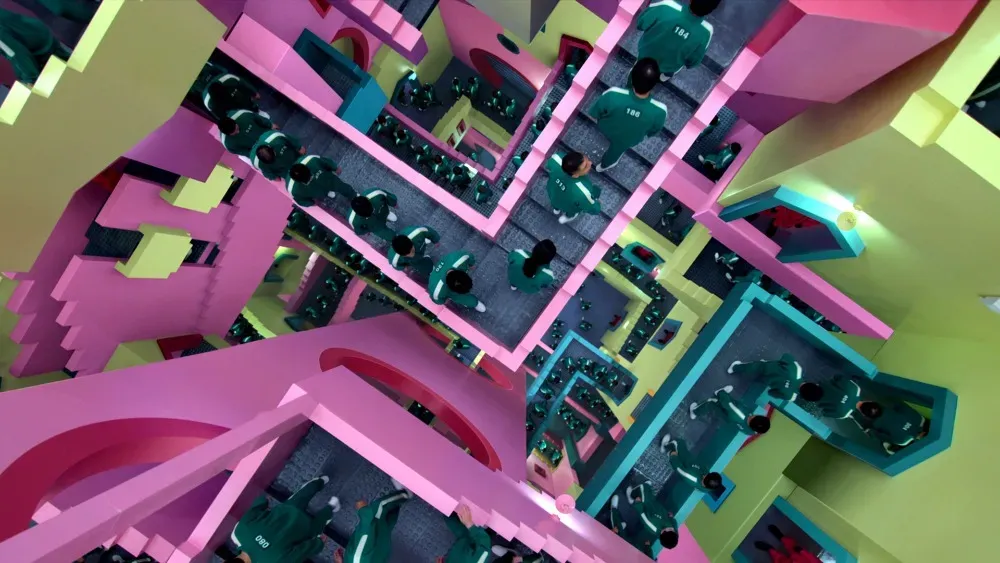

There’s a prevailing consensus that this season of Squid Game is, as much as hundreds of corpses can be, relatively boring. Compared to the first season, critics and viewers have found the plot slow, the dynamics repetitive, perhaps simply “a vehicle for more of the same high-design carnage.” Haven’t we seen this all before? But while one’s mileage may vary on the superficial action of a Squid Game season – and whether or not re-runs of Red Light Green Light could be infinite, grotesque entertainment – the show has always been just as much about the ideology as the plot.

Confronted with a repetition of the same brutality of capitalist exploitation, however, some critics have assumed that there must be some new message at hand, while others have found the old message tired.

The prevailing interpretation of the new season is that creator Hwang Dong-hyuk is turning his ire towards the players themselves, challenging our sympathy with them as individuals and undermining our faith in our collective political ideals.

Brian Phillips, in The Ringer, suggests this season is “asking whether people even want to escape—in other words, whether humanity can be redeemed at all.” In Phillips’ assessment, “[i]f the theme is market economics exploit vulnerable people, Hwang isn’t content to write a story that simply illustrates this idea. Instead, he challenges it. He gives us a set of vulnerable people who seem willing to exploit themselves.” Roxana Hadadi, at Vulture, senses “an encroaching bitterness toward the proletariat” in this season. For Hadadi, along with remnants of the show’s take on the “perniciousness of capitalism,” this season is about “conceptualizing how grueling it is to craft a society that protects and provides for everyone.” She reads the show as “painting self-government as an act of insanity” where “[t]he greatest villain of all…might be democracy itself.” Rebecca Sun, in an op-ed at The Times, recognizes the cruelty that forces players into the game, but when they are there, she concludes that “the second season is all about the toll of tribalism: how the push to pit ourselves against one another in a winner-take-all political battle leads to destruction and despair for all.”

Meanwhile, Times critic James Poniewozik questions why Hwang has spent another season retreading the horrors of the compound. “Somewhere around the umpteenth stabbing and machine-gun execution,” he writes, “I had to wonder if this was supposed to be fun, and at what point its social critique just becomes fatalism.” He suggests that the repetition of this second season is, uh, something like looking for a secret island in a patch of ocean you’ve already searched. “If the blood sport is the natural culmination of an economic deathmatch that everyone everywhere competes in, then the solution to this larger problem must lie outside the game,” he writes. He offers that Squid Game could follow the lead of the “Hunger Games” and branch out towards “the dystopian larger society whose existence sustains and depends on the cruel spectacle.”

I think that these interpretations, from the best critics we’ve got, are all making the same mistake. The ideology here is the same: it’s our reaction that may be different. They are now considering the game the world, when it is the world that’s the game.

There are a certain set of lessons you can take from this season if you consider the game a world unto itself – lessons Hadadi describes as a “bloody, cynical worldview.” You might conclude that people are callous and selfish, dumb or untrustworthy, willing to freely choose their own exploitation and death. You might also judge that cooperation is impossible and democracy unwise, that the prospect of peaceable society is nil, that we might as well all be fatalists ourselves. How else could we understand these contestants opting time after time to risk death each game, to kill one another between rounds, to opt out of a revolutionary moment? If we’re taking the compound as a literal microcosm or a perfect philosophical analogy for the outside world then individual behavior does seem rotten and collective behavior as doomed.

But the game isn’t apart from the world, it is one particular part of it. The people who’ve arrived there, both as players and as workers, by and large come from one kind of structural and systemic violence only to enter into another, more literal, kind of structural and systemic violence. Given the debts and deprivation they carry from civilian life and the controls and threats they face on the island, there’s no way we could meaningfully consider them agents “crafting a society” empowered with “self-government.” Democracy in a cell at gunpoint is no real kind of democracy. No one here is freely “willing to exploit themselves”: people are here because of the “dystopian larger society” that already exists and we are supposed to take as given. They do not “pit ourselves against one another in a winner-take-all political battle”: they are pit. The tribalism in the compound is not based on ethnicity or religion or geography – players here have to find out they are, in regular life, neighbors in the same part of Seoul. The tribalism is constructed by the game makers, a wedge between Xs and Os explicitly for the purposes of intraclass conflict. These contestants face background social conditions that made their misfortune or mistakes damning for their own survival and, now, in their attempts to survive they must make terrible and warped choices under oppressive conditions.

The lens is certainly more on the players (and workers) this season – we don’t see the spectator elite for a single frame – but I’m not convinced that the scrutiny is supposed to be. Instead, the scrutiny may be on us. Given a focus on the behaviors of the players, the show is asking how quickly we will forget the forces that brought these players here and the rules governing their brutal game. Whether intentional or not, this season is a test for how easily we will give up our attention on the structural when individuals and groups appear to behave badly within those structures. That, not coincidentally, is exactly the calculus we use to decide who our political systems will care for – which, if any, portion of our societies we believe deserve to be saved from economic ruin. That’s welfare dependent on work; that’s people with criminal convictions excluded from housing, food, and social security benefits. I see Hwang quietly setting us up: are we going to condemn the contestants in this TV show in the same way we condemn our fellow citizens?

And that set-up is on favorable terrain: it is always easier to judge the behaviors that we can see than the decisions and structures that influence and constrain those behaviors In both real life and the show, this means we invariably damn more and more people from the system rather than changing the system. Disguising this analysis in a competition makes for better TV – more costumes and gun battles – than a documentary about the political and economic history of South Korea behind Squid Game’s class system. And so, through a new focus this season, I think Hwang is testing us to see if we’ll resort to that same atomized outlook that produces our background conditions to begin with – our gaze looking down and around instead of up to the powers in control. As Hwang told The Hollywood Reporter “We think everyone’s our enemy. Everyone’s someone you’re against. On the other side of that, I think we ask less questions about our fundamental systems that have made us behave this way, and have created this kind of environment. I wanted to have the fight between the people reflect that.”

As a standalone season of television, perhaps Hwang was unsuccessful in that mission. After all, this message didn’t seem to land with most people while I’m here writing a thousand words trying to parse it. It may not be a perfectly calibrated test. Still, as Hwang conceptualized this season as part of one arc with Season 3 (coming sometime this year), my bet is that the resolution will make it clear where our sympathies were supposed to be and what our experience of this season signified. That we should be bored with the repetition of cycles of exploitation. That there are many, many tricks to make us focus on individual behavior instead of villainous conditions. That the game is not just on the island: this whole world is a game that we play, one we don’t often recognize we are shaped by, one whose rules are created by some but always contestable by others.