Why try?

Some thoughts on believing in action.

In the past few weeks, I have spent many hours trying – which is more than most but far less than some. While the majority of people have simply watched the horrors unfold in Gaza and Israel, I’ve been in chats and channels and meetings and protests trying to do something to stop them. Some, many of my friends, have done all that and much more: traveling across the country, working and thinking and moving constantly (at least when out of jail). They are the embodiments of trying.

These leaders and all people act out their convictions – a simple concept that we mystify as “activism” – for different reasons: a moral urgency for alignment; a spiritual or religions command; the simple need to express rage, pain, or love.

Even if I’ve occasionally reached for those, the truth is that the reason I’ve always needed is to believe the trying is going to be successful. For many years, I only understood success as an immediate victory over an opponent. Seeing so little of that happening, I was convinced that activism was for dopes – naive idealists, shouting in the wind. Even if I agreed with all these people, given the outcomes, I could never find a satisfying answer to that nagging question: why try?

In times like these, as the Israeli government demolishes Gaza without restraint or restriction, this question is unavoidable. It scratches at me again. If I am honest, I am not hopeful that the protests and actions in the US and across the world have a real impact on stopping further atrocities. I am doubtful that in the lucky instances where we see some success, we would be able to know it was due to our efforts. I would like to be wrong about our power, but every day seems to further clarify its limits.

And yet by now, I hold on to a theory for why we must try anyway. I want to share it — in part because it may be helpful to others who have felt this way and, in part, because reciting it helps me steady myself despite the deepening darkness.

Namely:

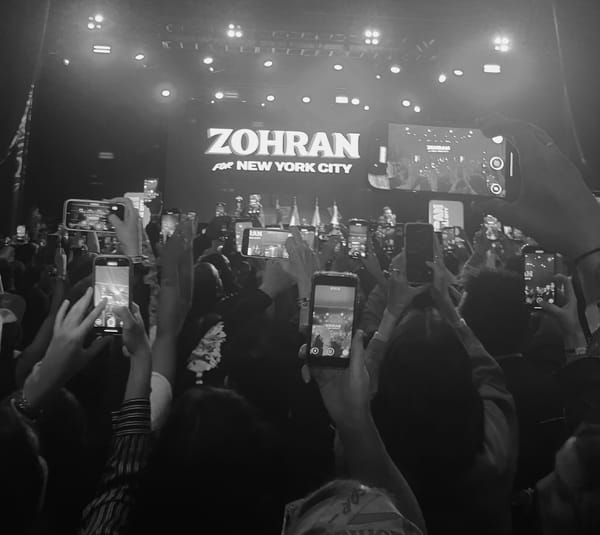

Our trying – our statements, our protests, our political pressure – proves the existence of an alternative. Today that alternative invites others to try. The massive protests we have seen these weeks are not aberrations, they’re results of much smaller protests that established the possibility and identities of resistance from the norm, and spread from growing movements that brought Palestinian freedom into much wider agitation. What we do now may not change what is happening, but it can certainly change how millions of people, full generations, understand and pass judgment on what is happening and who they are in relation to it. Ahead, our trying is proof for the future that what happened now was not inevitable. There was not unanimity on supporting genocide; the starvation of millions of people was not unquestioned; everyone was not behind a blind rampage of revenge.

If we can prove the existence of an alternative, and continue to do so repeatedly, there can be consequences for those who still insisted on injustice. Perhaps lost elections, maybe infamy and ostracization, even accountability. If we produce those consequences, then we can open spaces of power we may fill. We can have powerholders and politicians who are tryers themselves, so that sometime, years or decades or centuries from now, the decisions made for us are decisions we only once imagined. We try today so that, in a future, we aren’t the ones that have to.

Maybe that’s all wrong, or maybe (I hope) I’m wrong about our power, but this is what I have to believe in order to keep trying. As I do, there is at least some outcome guaranteed today: to exist for moments in smaller worlds where life is sacred and equality is commonsense, bonded together with people who, for whatever their reason, can’t stop trying either.